Hereditary Evils of the French Revolution: Nationalism (II)

|

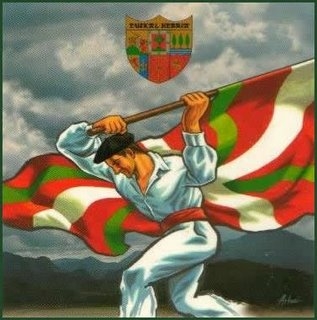

The Basque ikurriña flag: like the swastika in Nazi Germany,

a political party flag (PNV) becomes official for a territory (Basque

country autonomous community) |

2. Evil and Impossibility

Whether this legacy of the Revolution is an evil or not, I leave to the reader's judgment. A glance at contemporary history and daily newspapers suffices to show the consequences that nationalism has provoked and will predictably continue to provoke as long as the so-called right of self-determination is left unquestioned. It is enough to consider the present processes of disintegration (Basque or Catalan separatism, e.g.) and of integration (European Union, e.g.) to understand that this problem is unsolvable: national exclusivity demands its own State and at the same time repudiates political forms of higher complexity. By this logic, it is an absurdity to be Spanish and Catalan at the same time, since nationality is only meaningful insofar as it has a right to claim a State, and if it claims a State it cannot insert itself into another, if the idea of sovereignty is to be respected. Neither Catalan nor Spanish nationalists, both infected by revolutionary doctrine, can consent to this double bond. The former would see it as a capitulation to a Spanish State which they can never belong to (if they can come to be content with mere autonomy at certain points, it is a compromise of political opportunity, only a temporary silencing of an ideology that by definition cannot accept other than independence). The latter cannot accept a Catalan identity meaning anything more than a provincial sense of belonging to an administrative division: if it were understood in a truly national way it would pose a menace to the constituted Spanish State, precisely because they as well cannot consider the nation as something separate from the State. This apparently irreconcilable situation is perfectly comprehensible: both kinds of nationalists share the same doctrine, but differ in their appreciation of who makes up a people.

|

| Embrace of Vergara |

I leave it to the reader to judge nationalism as good or evil, but I will content myself by saying it is impossible: the complete fulfilment of the nationalistic ideal, where each nation has its own State, is not being stopped by the great powers of the status quo, but above all by its own logical impossibility. Because, as it has been said, the notion of national exclusivity that nationalism presupposes is not based on reality, it is not in accordance with the varied nature of the ascending associative phenomenon. Thus, it is impossible to find a truthful criterion that specifies who constitutes the people that is called to form a State. For, in the words of Francisco Elías de Tejada, peoples are not nations, but traditions:

“The present language uses the term nation to distinguish peoples, defining the nation by physical features or as expressions of will: geography, race, language, the plebiscite renovated on a daily basis...

As opposed to these explanations, tradition defines peoples as accumulated history, considering said physical factors insofar as they have had an impact in the historical tradition for what they are: but never as elements valid in themselves, directly and exclusively.” [1]

|

| Linguistic map of 1914 Europe |

3. The Illusion of the Vote

Thus established the logical impossibility of nationalism, I conclude by making an observation on its practical operating capacity, which I summarize in this statement: the right of self-determination is not a drive that underlies national and international policy, but rather a (false) theory that is used to legitimize a posteriori acts that are driven by something completely different. In other words, policy does not serve the principle of self-determination, it is this principle that serves policy.

|

Kuwait: defended in two wars

against Iraq by the U.K. and the U.S.A.

Zeal for self-determination or sea

access to the Gulf? |

|

|

Consider, for example, how this so-called right is only recognized insofar as it is instrumented through a referendum or plebiscite. A voting can never give a true image of reality, since it only takes into account the will of those who live in the present, forgetting those who belong to the past and the future. Since perpetuation and continuity is probably the backbone of the sociological reality of populations, it seems reasonable that when a vote is to be taken to “decide” if a nation exists or not they also be taken into account. Evidently, a referendum cannot do this. It is not even a true reflection of the opinion of the living, since it can easily change and be as legitimate in a particular moment in time as in another: if self-determination is truly based on the opinion of voters, the instrument destined to measure this opinion must certainly be sensible to these changes in time. Again, a single referendum cannot do this. Suppose Scotland calls a referendum of independence from the United Kingdom, and it fails. Then, next year, it calls another, and so on until the result is affirmative. By the same token, an independent Scotland should be voting year after year with the same regularity whether it wants to re-unite into the former United Kingdom.

What is more: a vote is an instrument that can have very different results depending on how it is prepared by the constituted authorities, the only ones who can call it (this issue will be dealt with more thoroughly, God willing, in a later entry). The time at which the vote is to take place, the options that are offered, and even the wording of the propositions are malleable factors that, dexterously handled by the few who have the legal power to do so, can determine with certain predictability what the result is going to be. This way, every vote ceases to be an expression of the collective will and becomes, in truth, an instrument to legitimize preconceived political measures. Democracy, then, becomes the power of constitutional engineering.

|

|

| Plebiscite (fixed) about annexation to Italy, in the film The Leopard: during Italian unification plebiscites (whose validity is questioned by some) would often be called in cities already conquered by garibaldine and Savoyard arms. |

|

[1] Francisco Elías de Tejada y Spínola, Rafael Gambra Ciudad, Francisco Puy Muñoz, ¿Qué es el carlismo?, 1971, ap. 61-62.

Hereditary Evils of the French Revolution: Nationalism (II) | Firmus et Rusticus (in English)

LinkBack URL

LinkBack URL About LinkBacks

About LinkBacks

Citar

Citar

Marcadores