Garcia Moreno – Model of a Catholic Statesman

Marian T. Horvat, Ph.D. Book review of Gabriel Garcia Moreno by Mary Monica Maxwell-Scott (London, 1914)

Reprinted by the Apostolate of Our Lady of Good Success (Oconomowoc, 2004), 185 pp.

Abbotsford House in Scotland, home of author and her great-grandfather Sir Walter Scott I first came across Gabriel Garcia Moreno, Regenerator of Ecuador by the Hon. Mrs. Mary Monica Maxwell-Scott some 20 years ago. It was a well-written historical work, as I expected, the author being the great-granddaughter of novelist Sir Walter Scott and an accomplished historical dramatist in her own right. (1) 1. Some works by the Hon. Mrs. Maxwell-Scott include Tragedy of Fotheringay (biography of Mary Queen of Scots), Madame Elizabeth of France 1764-1794, The Life of Madame de la Rochejaquelein, and St. Frances de Sales and His Friends.

It was a pleasant surprise, however, to find it an authentic work of piety. Mrs. Maxwell-Scott was obviously an admirer of the integrity and virile piety of that great Catholic statesman. I was also pleased to find her an enthusiast of the Catholic social order, supporting the views of the Catholic President of Ecuador who rejected the liberal ideas of Freemasonry that dominated 19th-century South American politics. Courageously going against the tide, Garcia Moreno insisted that Church and State work harmoniously together to build a prosperous nation.

Click here to purchase

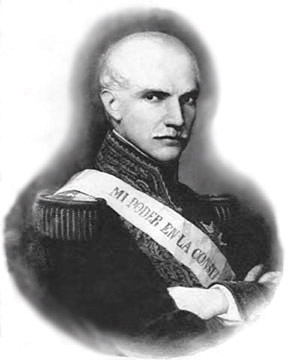

After 30 chaotic years of revolutionary activity, the Liberals in Ecuador had bankrupted the country and reduced it to near anarchy. By re-establishing the order of the Republic upon the rock of social Catholic doctrine, Garcia Moreno quite literally regenerated Ecuador, providing it peace and material progress during his ten years as president.

Why aren’t the name and achievements of such a great Catholic leader – the only President in the world to consecrate his country to the Sacred Heart of Jesus – better known throughout the Americas? The answer is quite simple: Because he was an anti-liberal Catholic. Instead of praise, the revolution spread vile slanders, labeling him a regressive theocrat, a tyrant, a, religious fanatic who imposed inquisitorial methods and repressed “progress.” These baseless accusations a contrario sensu give glory to Garcia Moreno because they clearly conflict with the known historical truth and are repeated only because he did not compromise with the Revolution.

The Concordat he signed with the Holy See as one of his first acts of government in 1862 made the State the protector and guarantor of the Church’s independence and granted it control over education. The liberals fumed; the people rejoiced. When he promulgated a new Catholic constitution in 1869 that made Catholicism the official religion of the State and required both candidates and voters for office to be Catholic, the liberals could not contain their fury and plotted several attempts on his life. After the public consecration he made of Ecuador to the Sacred Heart, he was condemned to die by the German Grand Council of Freemasonry (p. 152).

When he was elected to a third term in 1869, the rumors of an assignation attempt by the Masonic Lodges of neighboring countries became to fly. He was warned repeatedly, even by high Prelates, but he refused to run or hide. He wrote a letter to Pope Pius IX, mentioning the threats and asking his blessing “so as to live and die for the defense of our Holy Religion of this dear Republic, which God calls me again to govern … What greater privilege still, if your blessing were to obtain for me the grace of shedding my blood for Him, who being God, desired to shed His on the Cross for me?” (p. 156).

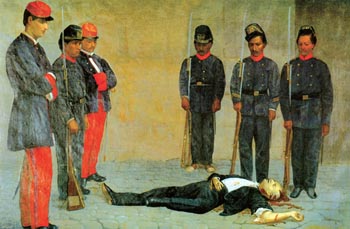

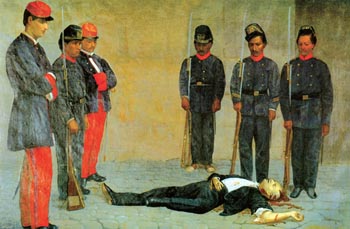

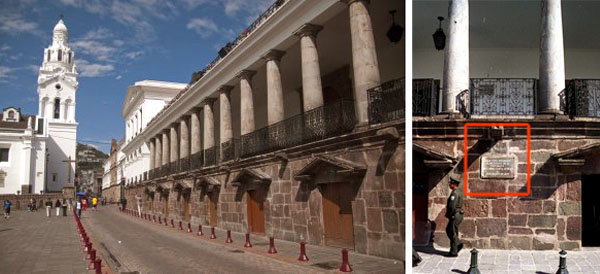

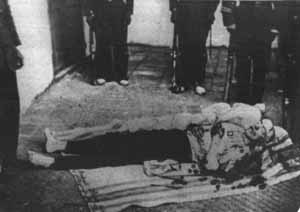

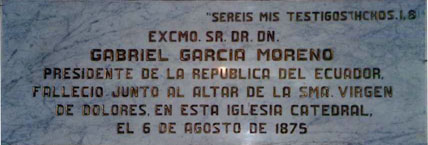

Some days afterward, as he left the Cathedral of Quito in midday after adoring the exposed Blessed Sacrament, Garcia Moreno was massacred at the hands of crude assassins paid by Freemasons, who viewed him as the greatest enemy to the liberal ideas they wanted to implant throughout the Americas. As one of the depraved murderers cut him down with a machete, he cried out “Die, destroyer of liberty!” Garcia Moreno responded, “God never dies.” These were his last words.

His mutilated body was carried into the Cathedral and laid at the feet of Our Lady of Dolors, where he died a quarter of an hour later. His left arm was severed and his right hand cut off by the blows of the machete; he had been shot six times. On his breast, they found a relic of the True Cross. Around his neck were scapulars of the Passion and the Sacred Heart, and his Rosary. In his pocket was a little memorandum written in pencil that day, “My Savior Jesus Christ, give me greater love for Thee and profound humility, and teach me what I should do this day for Thy greater glory and service.”

The liberals exulted and accelerated their campaign of calumny against him in the newspapers of the world. But the people of Ecuador grieved and his grateful country awarded him the titles of Regenerator of his Country and Martyr of Catholic Civilization. Pius IX, reigning at that time, eulogized him as a man who died “the death of a martyr, a victim to his Faith and Christian charity” (p. 163).

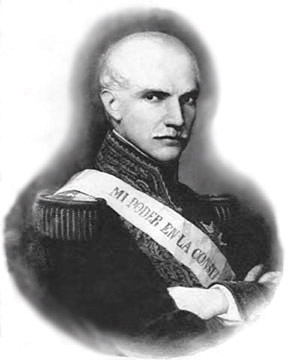

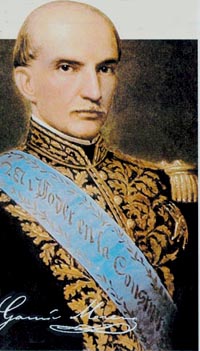

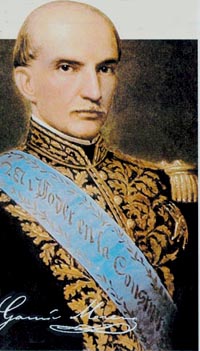

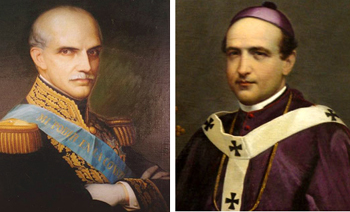

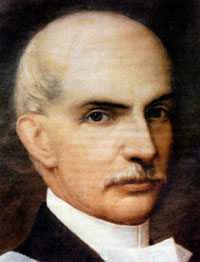

President Garcia Moreno Lies and slanders were the only weapons the Revolution had to use against Gabriel Garcia Moreno, because to this day none can deny that this superb administrator not only restored morals and good customs, but also put his country on a sound financial basis and made innumerable reforms and improvements. He established the first major network of public highways across the country. He reformed the military; he threw out corrupt government officials and reduced the taxes.

He reworked the judicial system and severely punished dishonest judges. He opened new schools and universities, placed them under the direction of religious orders, and established obligatory primary education. He introduced the latest science to the hospitals and eliminated the miserable conditions in prisons. He rid the country of brigands and thieves who endangered travel.

Far from viewing his policies as “oppressive” and “tyrannical,” as the liberal press depicted them, the people championed him as the “savior of Ecuador” and loved him as a saint. The peasants said of him: “He spared us neither punishments nor corrections, but he was a true Saint. He gave us big wages and great rewards. He would recite the Rosary with us, teach the Catechism, explain the New Testament, make us go to Mass and prepare us all for Confession and Holy Communion. Peace and plenty reigned in our farms because the mere presence of this excellent Caballero banished all evil” (p. 118).

Garcia Moreno’s mission: Foreseen by Our Lady of Good Success

One of the reasons I became interested in learning more about Gabriel Garcia Moreno was because Our Lady of Good Success spoke of him some 250 years before his presidency. As most of my readers know, Our Lady appeared to a Spanish Conceptionist sister in the 1600s and warned her of a crisis of world proportion that would afflict the Holy Catholic Church in the 20th century. She told her that heresies would abound, the light of Faith would be nearly extinguished, impurity would inundate the world and Church “like a filthy sea,” and the corruption of morals and customs would be almost complete. (2)

Know more

In an apparition of January 16, 1599, she spoke about Ecuador, which she predicted would become a Republic and need the sacrifice of heroic souls to sustain it in face of many public and private calamities. Then she referred to Garcia Moreno: “In the 19th century, there will be a truly Catholic president, a man of character whom God Our Lord will give the palm of martyrdom on the square adjoining this Convent. He will consecrate the Republic to the Sacred Heart of my Most Holy Son and this consecration will sustain the Catholic Religion in the years that will follow, which will be ill-fated ones for the Church. These years – during which the evil sect of Masonry will take control of the civil government – will see a cruel persecution of all religious communities.” (3)

2. See M.T. Horvat, Our Lady of Good Success: Prophecies for Our Times, (Los Angeles: TIA, 2000), pp. 53-9.

3. Ibid., p. 37. The governments of Generals Juan Flores (1839-45) and José Urbina (1851-2), Freemasons and cruel persecutors of the Catholic Church, sought to close the convents and monasteries and secularize all the State institutions. The “truly Catholic president” who consecrated the nation to the Sacred Heart in 1873 was Gabriel Garcia Moreno. His life and death stand as powerful evidence of the authenticity and veracity of the messages of Our Lady of Good Success. To predict with this kind of precision the place of death of the martyr-president is something only God can do. The realization of that prediction is obviously an important factor of credibility for the prophecies.

The life of Garcia Moreno, like the revelations of Our Lady of Good Success were relatively unknown outside of Ecuador for centuries. Now, his name comes to relevance with hers.

On an order from the Freemasons, Garcia Morena was attacked and killed outside the Governor's Palace

I believe Garcia Moreno has an important role in our times. Our Lady of Good Success warned about today’s crisis in Church and chastisement. But she also promised, through her intercession, a restoration of the Church and Christendom. Garcia Moreno is a model for all Catholic statesmen – present as well as those to come in a future restored Christendom.

He also provides a model for laymen of our days, inviting them to a life of action in the temporal sphere. Against the odds of success, Garcia Moreno disciplined himself, studied, and prepared himself to govern and act in temporal sphere. “I work 16 hours a day and if there were 48 hours in a day I would work for 40 without flinching,” he wrote to one of his friends during his exile in Paris in 1853, studying history, geology, and chemistry (p. 20). He did not know if Providence would give him the opportunity to apply that knowledge, but he acted with confidence despite the almost insurmountable obstacles he knew he would face.

He returned to Ecuador convinced that a strong Catholic man, with the assistance of Our Lord and Our Lady, could change the direction of the country, go against the tides of Liberalism, and make it an authentically Catholic nation. I am sure that many young idealistic men fighting a similar battle against Progressivism in our days can find inspiration in the life of Gabriel Garcia Moreno.

I was quite pleased, therefore, to learn that the Our Lady of Good Success Apostolate had recently reprinted the work by the Hon. Mrs. Maxwell-Scott to make it more readily available for the American Catholic public. This short biography will whet the appetite of those Catholics who seriously desire the restoration of a Catholic social order.

“Impossible in these days,” sardonic scoffers will say. It is the same objection that many doubters made to Garcia Moreno. To those who presented this aim as impossible, his invariable reply was this: “God never dies, God is, and that is enough. What is impossible to God?” Our answer should be the same.

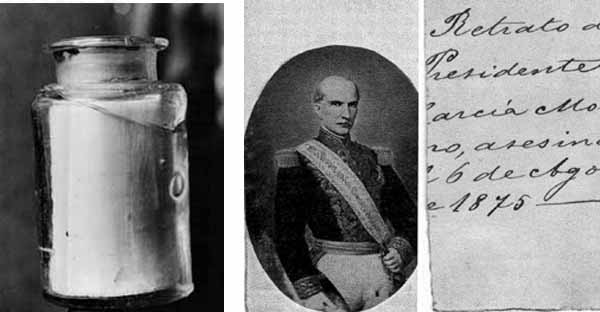

The “rule” of Garcia Moreno found after his death in his pocket.

The discipline and piety that governed the life of Gabriel Garcia Moreno is best revealed in the brief rule of life he wrote on the last page of his Imitation of Christ, a book he always kept with him. It was found in his pocket after his death. The rule reads:

Gabriel Garcia Moreno, President of Ecuador (1861-1865, 1869-1875)

“Every morning when saying my prayers I will ask especially for humility. Every day I will hear Mass, say the Rosary and will read, besides, a chapter from the Imitation, this Rule and the instruction added to it.

“I will endeavor to keep myself as much as possible in the presence of God, especially during conversations that I might not exceed in words. I will often offer my heart to God, principally before beginning any actions.

“Every hour I will say to myself: ‘I am worse than a demon and hell should be my dwelling place.’ In temptations I will add: ‘What would I think of this in my last agony?’

“In my room, never to pray sitting when I can do so on my knees or standing.

“Practice daily little acts of humility, as kissing the ground.

“To rejoice when I or my actions are censured. Never to speak of myself except to avow my faults or defects.

“To make efforts, by thinking of Jesus and Mary, to restrain my impatience and go against my natural inclinations.

“To be kind to all, even with the importunate, and never to speak ill of my enemies.

“Every morning before beginning my work, I will write down what I have to do, being very careful to distribute my time well, to give myself only to useful and necessary business, and to continue it with zeal and perseverance.

“I will scrupulously observe the law of justice and truth, and have no intentions in all my actions save the greater glory of God…

“I will go to confession every week…

“I will never pass more than an hour in any amusement, and in general never before 8 o’clock in the evening.”

Marian Horvat reviews Gabriel Garcia Moreno by Mary Maxwell-Scott

The news was flying right and left: “The President has been shot and killed.” “The scoundrel Rayo is the murderer.” In the confusion, an order was heard, “Kill the assassin!”

LinkBack URL

LinkBack URL About LinkBacks

About LinkBacks

Citar

Citar

After

After

Gabriel Garcia Moreno, heroic President of Ecuador, assassinated for his Faith and Christian Charity.

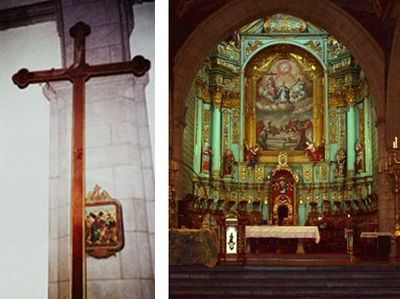

Gabriel Garcia Moreno, heroic President of Ecuador, assassinated for his Faith and Christian Charity. The cross carried by President Garcia Moreno during Ecuador's Holy Week procession.

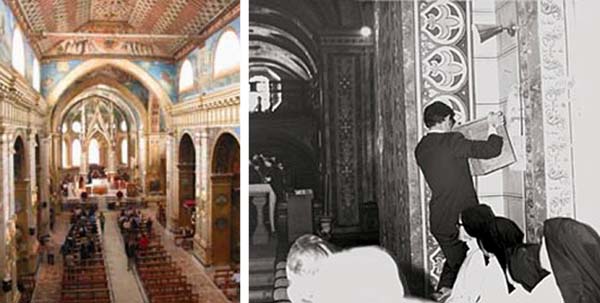

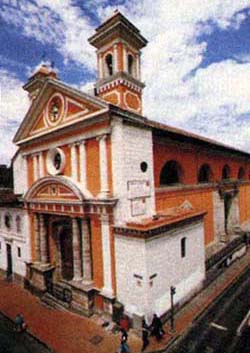

The cross carried by President Garcia Moreno during Ecuador's Holy Week procession. Garcia Moreno's tomb in the crypt of the Cathedral of Quito

Garcia Moreno's tomb in the crypt of the Cathedral of Quito

Marcadores