Liturgical Curiosities from Medieval Spain

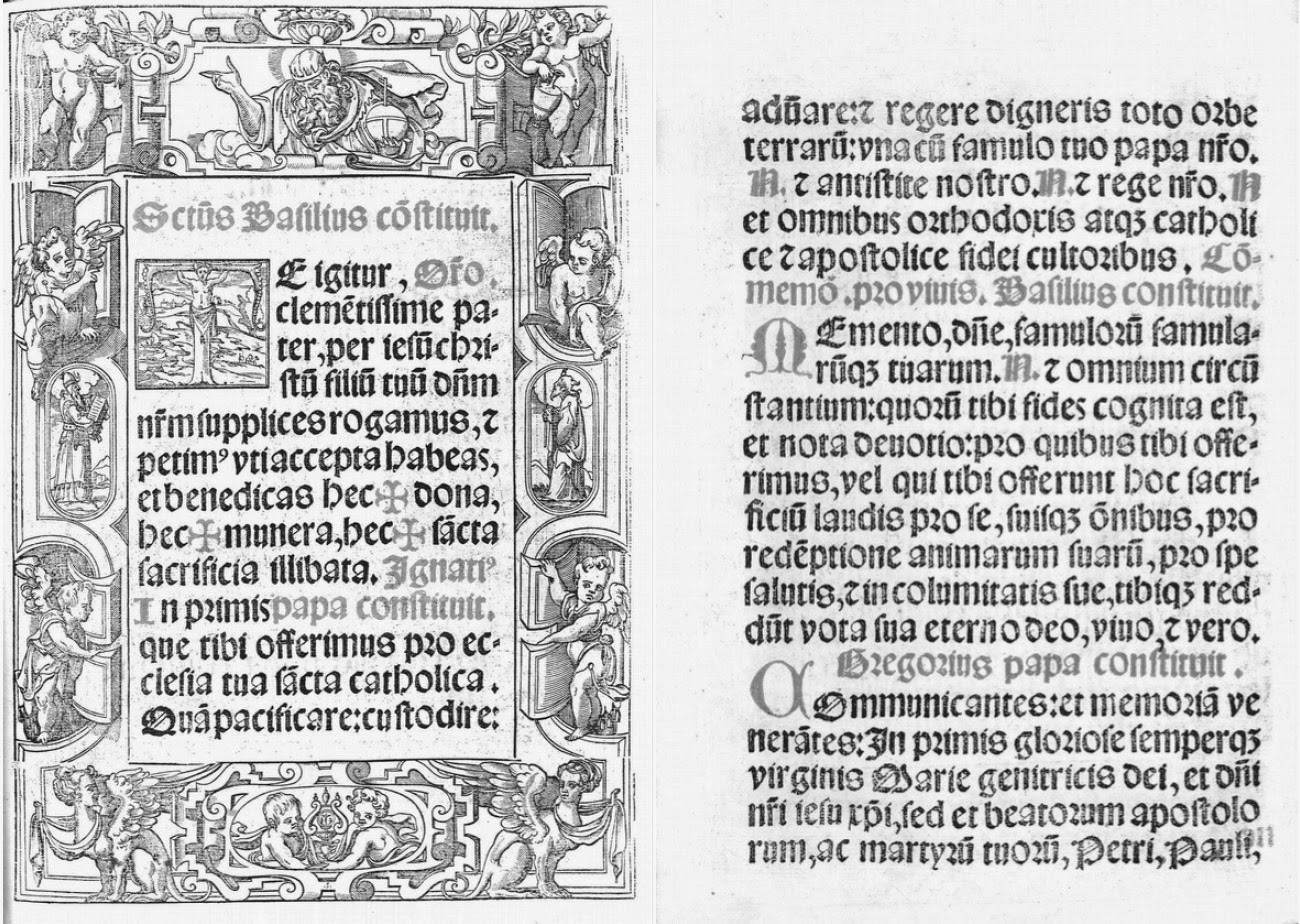

Gregory DiPippo In the course of researching my articles on the Theology of the Offertory, and specifically the offertories of the medieval Spanish uses of the Roman Rite, I came across an interesting custom in the way of printing certain Missals before the Tridentine Reform. I believe this custom may be completely unique to Spain; I have never seen anything like it in any of the great many other medieval Missals I have read through over the years. (I here use the term “medieval” in reference to the origin of these liturgical customs; the Missals themselves were printed in the Renaissance.) The examples I give here are from the Missal according to the Use of Seville, printed in that city in 1565, and that of Segovia printed at Venice in 1500.

In these missals, each part of the Canon of the Mass is labelled with its putative author, each of whom “constitutit – established” that that part of it be said. Where these attributions come from, I cannot imagine, and their inventor had some rather confused ideas about Church history. Except for St Basil, all of the supposed authors are called “Papa”, but there has never been a Pope named Ignatius, Maxentius, or Bricius. (This last is traditionally Anglicized as “Brice” when it refers to St Martin of Tours’ disciple and successor.) Of course, the word “Papa” was formerly used for other bishops beside the Pope, and it likely that “Pope Ignatius” means St Ignatius of Antioch. “Pope Maxentius” remains quite mysterious.

“Pope Bricius” on the other hand, is a legendary martyr and early bishop of Évora in Portugal, said to be a disciple of the first bishop of Braga, St Peter “de Rates”, who was in turn a disciple of the Apostle St James the Greater, converted when the latter was evangelizing Spain. The Missal of Seville attributes to Bricius the singular honor of having established the Institution Narrative; without positing any conscious fraud, we may conjecture that this pedigree was intended to confirm the Iberian peninsula’s bona fides for receiving the Faith from one of the chiefs among the Apostles. (Segovia, on the other hand, garbles the name as “Baccius”, but this may be a mistake of the Venetian printers.)

The attributions in order are:

Te igitur: St Basil (the Great. The Missal of Segovia adds for precision “at the fifth synod in the city of Antioch”.)

In primis quae tibi: “Pope Ignatius”

Memento of the living: Basil again (Segovia says Pope St Celestine I, 422-32)

Communicantes: Pope St Gregory the Great

Hanc igitur: Pope St Innocent (the First, 401-17)

Quam oblationem tibi: “Pope Maxentius”

Qui pridie: “Pope Bricius” (or Baccius)

Unde et memores: Pope St Sergius (the First, 687-701)

Supplices: Pope St Leo the Great

Memento of the dead: Pope St Calixtus (the First, 218-223)

Nobis quoque: Pope St Pelagius (the First, 551-565; or the Second, 579-90, Gregory the Great’s predecessor)

Per quem haec omnia: Pope St Xystus (the Second, 257-58, the Xystus mentioned in the Communicantes)

The Missal of Seville gives three different tones for the singing of the Our Father, but says nothing about its author, presumably understood to be the Lord. The Missal of Segovia, on the other hand, puts before it the words “Gregorius dialogus constituit – Gregory the Dialogist established”, i.e., that it be sung after the Canon. (“Dialogus” is the title by which Pope Gregory the Great is known in the East, referring to his collection of Saints’ biographies, the Dialogues.) Both Missals agree in attributing the Libera nos to Pope St Urban I, 222-230.

Despite the historical confusion, and the fact that none of these attributions rests on any evidence, several of the Saints named herein are traditionally known as the authors of various parts of the liturgy, or the originators of certain liturgical customs. The anaphora attributed to St Basil the Great is used in the Byzantine Rite on a handful of days, including the Sundays of Lent (but not Palm Sunday), Holy Thursday and Holy Saturday. St Ignatius of Antioch is traditionally said to have instituted antiphonal singing in church, after a vision of angels chanting thus in Heaven. Among Gregory the Great’s many contributions to the liturgy is the addition to the Canon of the words “diesque nostros … grege numerari”; he also did move the Lord’s Prayer to its place after the Canon. The Byzantine Rite attributes to him the Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts which is celebrated on certain weekdays of Lent, and commemorates him at the end of that service. Sergius I added the Agnus Dei to the Mass, and Leo the Great added the words “sanctum sacrificium, immaculatam hostiam” to the Canon. Calixtus I is said to have instituted, or rather formalized, the Ember Days, which Leo (two centuries later) believed to date from Apostolic times.

The attribution of the final part of the Canon (“Per quem haec omnia”) to Pope St Xystus II may be related to a custom associated with his feast day, August 6th. On that day, grapes were traditionally blessed between the end of the Nobis quoque and the Per quem haec omnia, also the traditional place for the blessing of the oil of the Sick on Holy Thursday. Although the blessing of the grapes, which is also observed by the Eastern churches, long predates the Western adoption of the feast of the Transfiguration, the Missal of Seville gives a charming explanation of why it is done on that date. “It must be noted that on this day, the Blood of Christ is confected from new wine… (and) this is the reason. On the day of the (Last) Supper, the Lord Jesus said to the Apostles… ‘Amen I say to you, I will not drink from henceforth of this fruit of the vine, until that day when I shall drink it with you new in the kingdom of my Father.’ (Matthew 26, 29) Therefore, because He said “new”, and the Transfiguration pertains to that state which He had after the Resurrection, new wine is sought on this feast.”

New Liturgical Movement

LinkBack URL

LinkBack URL About LinkBacks

About LinkBacks

Citar

Citar

Marcadores