Estudio del obispo Tissier de Mallerais (FSSPX) sobre la herméutica y teología del papa Benedicto XVI, muy interesante para entender la manera de pensar del Papa y algunos puntos de su manera de actuar.

Publicado originalmente en francés, ahora está en inglés. Copio entero, pero el texto son 81 páginas, ojo.

--------------------

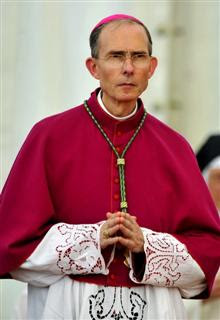

Bishop Bernard Tissier de Mallerais' "Faith Imperiled by Reason: Benedict XVI's Hermeneutics"

True Restoration is proud to present a translation of Bishop Tissier's lengthy article of last summer on the hermeneutics of Benedict XVI. Due to online formatting, the footnotes in the original document are endnotes in this edition. Also, in the original, His Lordship refers to a book called The Christian Faith of Yesterday and Today. It is known in the United States as Introduction to Christianity. We have changed the references thusly.

In his Afterword, the Bishop thanks Frs. Benoit de Jorna and Jean-Michel Gleize, two of the four men in the SSPX's delegation to Rome. Due to their consultation and collaboration in this lengthy article of Bishop Tissier, it is reasonable to assume that they share his concerns and conclusions, and that these important matters are being discussed in Rome.

Because this renders at over 80 pages, with over 200 citations, if reading and printing from your computer is burdensome, you may purchase a printed copy from True Restoration Press, which is flat bound for greater ease of study. If you read French, you can buy the original issue of Le Sel de La Terre from the Dominicans.

Introduction

Dr. Peter Chojnowski

Those who remain attached to the Catholic Faith as articulated by all the great dogmatic Councils of the Church are greatly indebted to His Excellency Bishop Bernard Tissier de Mallerais for this article, published just last summer in the French Dominican publication Le Sel de la Terre and just translated into English. The fight we are in for Catholic Tradition is not a fight over ceremonies and rituals, which some happen to like and others happen not to like. The Sacred Rites of the Church are “sacred” precisely because they express and apply to the concrete lives of the Faithful, the truths and grace which even God the Son did not “make up,” but were, rather, revealed to Him by His Father in Heaven. This article, which compares the theology of Josef Ratzinger (Benedict XVI) to that of the traditional theology of the Church as articulated by the Popes, the Fathers, and the Doctors, is truly a comprehensive study for all those interested in the doctrinal issues now being discussed behind closed doors. Since the Conciliar Church has decided to accept the personal theology of each new pope as its current interpretation of the fundamentals of the Faith, it is absolutely essential for real Catholics to understand the Modernist Revolution in its current stage. Please spread this article far and wide. The text is long, however, the reader should make it to the end in order to understand how the New Theology attempts to transform the most fundamental doctrines of the faith.

After reading this fascinating essay, anyone who thought that “reconciliation” between Catholic Tradition and Vatican II theology is right around the corner will have to think again!

January 2010

******************

Faith Imperiled by Reason

Benedict XVI’s Hermeneutics

Bishop Bernard Tissier de Mallerais

From La Sel de Terre, Issue 69, Summer 2009

Translated by C. Wilson

Translator’s Note: I have decided rather to preserve the Bishop’s slightly familiar writing style than to convert the tone of the article to something purely academic.

· Foreword

· Introduction

· The Hermeneutic of Continuity

· Joseph Ratzinger’s Philisophical Itinerary

· Joseph Ratzinger’s Theological Itinerary

· An Existentialist Exegesis of the Gospel

· Hermeneutic of Three Great Christian Dogmas

· Personalism and Ecclesiology

· Political and Social Personalism

· Christ the King Re-envisioned by Personalism

· Benedict XVI’s Personalist Faith

· Skeptical Supermodernism

· Epilogue: Hermeneutic of the last ends

· Afterword: Christianity and Lumieres

Foreword

This is Benedict XVI’s hermeneutic[1]:

– First it is the hermeneutic which a pope proposes for the second Vatican Council so as to obtain for it, forty years after its conclusion, reception into the Church;

– Next it is the hermeneutic, very much like modern reason, which the Council and conciliar theologians propose for the faith of the Church, though these have opposed each other in a mutual exclusion since the Enlightenment, in order to reduce their opposition;

– Last, it is the hermeneutic of the thought of a pope and theologian who attempts to make faith reasonable to a reason trained to refuse it.

*

The triple problem which, according to Benedict XVI, hermeneutic ought to have resolved at the Council and which it must still resolve today is the following:

1. Modern science, with the atomic bomb and a consumerist view of man, violates the prohibitions of morality. Science without conscience is nothing more than the ruin of the soul, said a philosopher. How to give science a conscience? The Church in the past was discredited in the eyes of science by its condemnation of Galileo; by what conditions can she hope to offer positivistic reason ethical norms and values?

2. Confronted by a laicized, ideologically plural society, how can the Church play her role as seed of unity? Certainly not by expecting to impose the reign of Christ, nor by restoring a false universalism and its intolerance, but by making an allowance for positivistic reason to challenge, in a fair competition, Christian values, duly purified and made palatable for the world which emerged after 1789, that is to say, after the Rights of Man.

3. Faced with ‘world religions’ better understood and more widespread, can the Church still claim exclusivity for her salvific values and a privileged status before the State? Certainly not. However, she wishes only to collaborate with other religions for the sake of world peace, by offering in concert with them, in a ‘polyphonic correlation,’ the values of the great religious traditions.

These three problems make no more than one: Joseph Ratzinger estimates that to a new epoch of history there must correspond a new relation between faith and reason:

“I would then willingly speak,” he has said, “of a necessary form of correlation between reason and faith, which are called to a mutual purification and regeneration.”[2]

Asking pardon of my reader for having perhaps anticipated my conclusion, with him I have just entered my subject by the back door.

Introduction

Pope Benedict XVI’s speech to the Roman curia on December 22, 2005 appeared to be the programmatic speech of a new pontiff, elected pope the preceding April 19. It closely resembles his inaugural encyclical.

I am going to try to extract its ideas from it by force, then to analyze them freely. I thus offer to my reader a route of exploration through the garden of conciliar theology. Three avenues emerge at once:

1. Forty years after the close of the Council, Benedict XVI recognized that ‘the reception of the Council has taken place in a rather difficult manner.’ Why? he asks himself. ‘Well, it all depends on the just interpretation of the Council or—as we would say it today—on its just hermeneutic.’ Side by side with a ‘hermeneutic of discontinuity and rupture’ on the part of traditionalists and progressives, there is ‘the hermeneutic of reform, of renewal in continuity.’ This continuity is ‘the continuity of a Church which is a unique entity. […] It is an entity which grows with time and which develops itself, remaining always the same—the unique entity which is the people of God on its pilgrimage.

2. Such was the Council’s intention: to guard the deposit of the Faith but to ‘present [it] in a manner which corresponds to the need of our time’ (John XXIII, opening speech to the Council). Benedict XVI explains:

This commitment with a view to expressing in a new fashion a determinate truth demands a new reflection upon it and a new vital connection with it […]. The new way of speaking can only develop if it is born from a conscious understanding of the faith which is expressed and […], on the other hand, if the reflection upon the faith demands equally that one live this faith.

3. Thus, to present a living faith, fruit of a vital new experience, was ‘the program proposed by Pope John XXIII, extremely necessary, as it is precisely the synthesis of fidelity and of dynamism.’

*

The Council’s hermeneutic, then, stands upon three principles which follow one upon the next:

– The subject of faith, with his reason, is an integral part of the object of faith.

– Thus, he must look for a new vital connection of reason with faith.

– Hence there is implemented a synthesis of fidelity and dynamism.

What sort of synthesis is this? The Council explains: to college ‘the requests of our times’ and ‘the values most prized by our contemporaries’ and, after having ‘purified’ them, ‘to bind them to their divine source’ (Gaudium et Spes, n. 11), that is to say, to introduce them to Christianity along with their philosophy. But to do this, the Church must for her part, as the Council determined it, ‘to revisit and equally to correct certain historical decisions’ (Benedict XVI, speech of December 22, 2005).

Such is the hermeneutical program which must be mutually imperative for reason and faith.

I will not attempt either an analysis or a synthesis of Benedict XVI’s thought, of his inspiration so eclectic and mobile. Professor Jacob Schmutz, in twelve sessions with the Sorbonne University, during 2007-2008, detailed its components: secularization, Christianity as vera philosophia[3], the human personality irreducible in nature, the Enlightenment (Aufklärung) who need God to limit their passion for independence, the historical contingencies which keep the conscience from seeing, etc.

In this extremely rich body of thought, I will content myself with outlining an extremely reduced philosophical and theological course, according to the custom of the initiate, guided by the idea of hermeneutic as by Ariadne’s thread.

In my progress, I will let Benedict XVI speak, sometimes commenting in a polemical manner, for I have chosen such a style with care for brevity, suitable to this unpretentious journal.

When I cite his writings earlier than his sovereign pontificate, I attribute them with all respect and truth to ‘Joseph Ratzinger.’ His work, Introduction to Christianity, reproduces the course of the young professor from Tubingen and, prepared in French in 1969, was reedited in 2005 with a preface from the author, who fundamentally confirms his writing: ‘The fundamental orientation,’ he wrote, ‘was correct; that is why today I dare to place this book again in the reader’s hands.’

*

Several texts will whet my reader’s hermeneutical appetite. They are a little compendium of the developments which follow.

1. Concerning the corrective revisitation of Tradition

My fundamental impulse, precisely from the Council, has always been to free the very heart of the faith from under any ossified strata, and to give this heart strength and dynamism.[4]

Vatican Council II, with its new definition of the relation between faith and the Church and certain essential elements of modern thought, has equally revisited and corrected certain historical decisions; but in this apparent discontinuity, it has in return maintained and deepened its essential nature and its true identity.[5]

2. Concerning the purifying assimilation of modern philosophy

To assimilate into Christianity [modern] ideas born into a new world, often hostile and even now charged with an alien spirit, supposes a labor in the depths, by which the permanent principles of Christianity would take up a new development in assimilating the valuable contributions of the modern world, after having decanted then, purifying according to need.[6]

Certainly the philosophy of being, the natural metaphysics of the human spirit serves as instrument of faith for making explicit what it contains implicitly[7]: on the other hand, no philosophy can pose as partner of faith in ‘perfecting doctrine and faith like a philosophical invention for human minds.’[8]

Chapter 1

The Hermeneutic of Continuity

The Christian Faith of Yesterday and Today: the ‘why’ of hermeneutics

‘What is constitutive of faith today?’ Such is the question which Joseph Ratzinger posed in 1973, during a group ecumenical discussion, and which he posed as the first question of his book, The Principles of Catholic Theology.[9] ‘The question is ill framed,’ he amends; ‘it would be more correct to ask himself what, out of the collapse of the past, still remains today a constitutive element.’ The collapse is scientific, political, moral, even religious. Must one allow for a philosophy of history which accepts ruptures in faith as relevant, each thesis possessing its meaning as one moment from a whole? Thus, to paraphrase Ratzinger, ‘Thomistic as well as Kantian interpretation of Christian fact each has its truth in its own historical epoch but only remains true if one abandons it when its hour is finished, so as to include it in a whole which one constructs as a novelty.’

Joseph Ratzinger seems to dismiss this dialectical method precisely because it results in a new truth. It is not necessary to synthesize irreconcilables, but to find what continuity exists between them. Let us then find what permanence of Christian faith there is in the fluctuations of philosophies which have wished to explain it. Such is the theme of the professor of Tübingen’s work, Introduction to Christianity.[10]

Since reason seems to evolve according to diverse philosophies and since the past of such an evolution adapts itself to the faith, the connection between faith and reason must be periodically revised so that it will always be possible to express the constant faith according to the concepts of contemporary man. This revision is the fruit of hermeneutic.

Faith at risk from philosophy

When Saint John, and the Holy Ghost who inspired him, chose the name ‘Word,’ in Greek Logos, to designate the person of the Son in the Holy Trinity, the word had been until then as ambiguous as possible. It commonly designated formulaic speech. Heraclitus, six centuries before John, spoke of a logos measuring everything, but that meant the fire which burns and consumed all. The stoics used this term to signify the intelligence of things, their seminal rational (logos spermatikos) which merged with the immanent principle of organization in the universe. Finally Philon (13 BC – 54 AD), a practicing Jew and Hellenist from Alexandria, saw in the logos the supreme intelligibility ordering the universe, but much inferior to the unknowable God—that of Abraham and of Moses.

John seizes a Greek word. He wrests it, in a manner of speaking, from those who have used it in ignorance or by mistake. From the first words of the prologue to his Gospel, he gives to it, he renders to it rather its absolute meaning. It is the eternal Son of God who is His word, His Logos, His Verbum. And this Word is incarnate […]. Thus, the Revelation made to the Jews makes an effort, from its very beginnings, to express itself in the languages of Greek philosophy, without making any concession to it.[11]

Thus the faith expressed in human concepts is inspired Scripture; the faith explained in human concepts is theology, science of the faith; finally, the faith defined in human concepts is dogma. All these concepts have a plebian or philosophical origin, but they are only employed by faith once decanted and purified of all original, undesirable philosophical stench.

At the cost of what hesitations and what labors have the Fathers and the first councils resolved, when faced with heresies, to employ these philosophical terms and to forge new formulae of faith so as to clarify the gift of revelation! The use of the philosophical term, ousia (substance), hypostasis, prosôpon (person), to speak the mysteries of the Holy Trinity and of the Incarnation is accompanied by a necessary ‘process of purification and recasting’ of the concepts which these words signify.

It is only once extracted from their philosophical system and modified by a maturation in depth, then sometimes at first condemned because of their still inadequate content (monarchy, person, consubstantial), then understood correctly, admitted at last and qualified for application (but only analogically), that these concepts can become carriers of the new consistency of the Christian faith.[12]

These facts demonstrate that, far from expressing itself in the philosophy of the epoch, the faith must extricate itself from false philosophies and itself forge its own concepts. But is this to be extricated from all philosophy and to rest itself on a simple ‘common sense?’

With Father Garrigou-Lagrange, I will further respond to this question by showing that dogmas express themselves in the language of the philosophy of being, which is nothing besides a scientific instance of that common knowledge

Hermeneutics in the Patristic School

It was with repugnance, even, that the councils would consent to add precisions to the symbol of faith from the Council of Nicaea (325) which itself seemed sufficient to exclude every heresy. The council of Chalcedon (451), against the monophysite heresy, resolved to proceed to a definition (horos) of the faith, a novelty. A little after (458), the bishops would conclude that Chalcedon was no longer a extensive enough interpretation of Nicaea. The word, interpretation (hérmènéia), was also used by Saint Hilary (Syn. 91) when speaking of the Fathers who, after Nicaea, had reverently interpreted the propriety of consubstantial. It was a matter neither of a new reading nor of a revision to the symbol of Nicaea, but of a more detailed explanation. Such is, in consequence, the meaning of the hérmènéia achieved by Chalcedon. Later, one Vigilius of Thapsus would affirm that it was necessary, when faced with newly prepared heresies, to ‘bring forth new decrees of such a type that, even so, whatever the preceding councils have defined against the heretics remains intact.’[13] Then, Maximus the Confessor declared that the Fathers of Constantinople had only confirmed the faith of Nicaea against those who sought to change it for themselves to their own meaning: for Maximus, Christ subsisting ‘in two natures’ is not ‘another profession of faith’ (allon pistéôs symbolon), but only a piercing (tranoûntes) look at Nicaea, which, by interpretations and subsequent fashionings (épéxègoumenoi kai épéxergazoménoi), must still be defended against deformative interpretations.[14]

Thus, the hermeneutic (hérmènéia) that the Fathers practiced for the earlier magisterium was clarified as far as its end and as far as its form.

As far as the end, it is no matter of adapting a modern mentality, but of combating this modern mentality and of neutralizing the impression of modern philosophies upon the faith (it is in fact the characteristic of heretics to bring the faith to modern philosophical speculations which corrupt it). It is not any more a matter of justifying the old heretics in the name of a better comprehension of the Catholic formulae which have condemned them!

As far as the form, it is no matter of proposing modern principles in the name of the faith but of condemning them in the name of this same unchanged faith. In summary, the revisionist hermeneutic of Joseph Ratzinger is a stranger to the thought of the Fathers, There are, therefore, grounds for reviewing it radically.

The Homogenous progress of dogmas

It belongs to Saint Vincent of Lérins to have taught, in the year 434, the homogenous development of dogma, always by increase in explicitness but never by mutation:

It is characteristic of progress that each thing be amplified in itself; it is characteristic of change, on the other hand, that something be transformed into something else. [...] Whenever some part of the essential seed grows in the course of time, then one rejoices in it and cultivates it with care, but one never changes the nature of the germ: then is added to it, certainly, its appearance, its form, its clarity, but the nature in each genus remains identical.[15]

In the same sense, in 1854 Pius IX, citing the same Vincent of Lérins in the bull defining the Immaculate Conception, and speaking of the ‘dogmas deposited with the Church,’ declared that she ‘devotes herself to polishing them in such a manner that these dogmas of heavenly doctrine receive proof, light, clarity, but retain fullness, integrity, propriety, and that they increase only in their genus, that is to say, in the same dogma, the same meaning and the same proposition’ [DS 2802].

According to this progress in clarity, dogmas do not progress in depth—a depth of which the Apostles have already received the plenitude—nor in truth, that is to say, in their aptness to that part of his mystery which God has revealed. The progress sought by theology and by the magisterium is that of a more precise expression of the divine mystery as it is, immutable as God is immutable. Concepts, always imperfect, could always be refined, but they would never fall out-of-date. A dogmatic formula, therefore, never has anything to do with, nor ever has to earn the vital reaction of the believing subject, but it would have everything to lose in doing so. It is rather that subject who must, on the contrary, efface himself and disappear before the objective content of dogma.

Return to the objectivity of the Fathers and the councils

Far from being obliged to take on in turn the successive, temporary forms of human subjectivity, the dogmatic effort is a labor of perseverance for the sake of making revealed truth objective upon its base of the gifts of Scripture and Tradition. It is a work of purge from the subjective in favor of an objectivity as perfect as possible. This work of purification is not in the first place an extraction of the heterogeneous so as to regain the homogenous, even though it can be this when faced with heresies and doctrinal deviations. The essential operation of dogmatic development is the effort to reassemble what is dispersed, to condense the diffused, to eliminate metaphors as far as possible, to purify analogies so as to make them more suitable. Nicaea’s consubstantial and Trent’s transubstantiation come from such successful reductions.

Inevitably, dogmatic reduction deviates from scriptural depth: consubstantial will never have the depth of one word from Jesus, such as this: “Who sees me, sees the Father” (John 14, 9). In this word, what an introduction to an unfathomable abyss! What a source for interminable questions! What space for contemplation! And nonetheless, what progress in precision belongs to consubstantial! What a fountain of theological deductions! There is, it seems to me, Joseph Ratzinger’s whole gnoseological difficulty: torn between the dogmas which he must hold with an absolute stability and the inquisitive quest of his mobile spirit, Joseph Ratzinger never achieves the reconciliation of the two poles of his faith.[16]

When will the affirmation of the ‘I’ efface itself before the ‘Him’?

A new reflection by a new vital connection?

It is this effacement of the believing subject which Benedict XVI energetically refuses. For him, the evolution of the formulation of the faith is not the search for better precision, but the necessity of proposing a new and adapted formulation. It is novelty for novelty’s sake. And the adaption is an adaption to the believer, not an adaption to the mystery. All this fits with John XXIII’s syllogism, from the presentation of the program of Vatican II in his opening discourse:

From its renewed, serene and tranquil adherence to all the teaching of the Church in its integrity and its precision […], the Christian, Catholic and apostolic spirit of the whole world waits a leap forward toward a doctrinal penetration and formation of consciences, in the most perfect correspondence of fidelity to the authentic doctrine, but also: this doctrine studied and explained through the forms of investigation and the literary formulation of modern thought. One, in fact, is the substance of the ancient faith from the depositum fidei, the other the formulation of its surface: and it is of the later that one must, if there be need, take great care, by weighing everything according to the forms and the proportions of a magisterium whose character is above all pastoral.[17]

Such indeed was the Council’s task, Benedict XVI says: the modern reformulation of the faith; according to a modern method and following modern principles, then according to a new method and after new principles. For there is always method, on the one hand, and principles on the other. To apply this method and to adopt these principles should still be the Church’s task forty years later:

It is clear that this commitment in view of expressing in a new manner a determinate truth needs a new reflection upon that very truth and a new vital connection with it. It is equally clear that the new way of speaking can only mature if it is born from a conscious comprehension (Verstehen) of the expressed truth, and that on the other hand the reflection upon the faith demands just as much that one live that faith.[18]

There is the whole revolution of the magisterium implemented by the Council. Preoccupation with the subject of faith supplants care for the object of faith. In place of simply seeking to make dogma precise and explicit, the new magisterium will seek to reformulate and adapt it. In place of adapting man to Go, it wishes to adapt God to man. Do we not then have a subverted magisterium, an anti-magisterium?

The Method: Dilthey’s historicist hermeneutics

Where to find the method for this adapted rereading of dogma? A German philosopher who has influenced German theology and whose mark is found upon Joseph Ratzinger must intervene: Wilhelm Dilthey (1833-1911), father of hermeneutics and of historicism.

Hermeneutics, as we have seen, is the art of interpreting facts or documents.

Historicism then, wishes to consider the role of history in truth. For Dilthey, as for Schelling and Hegel who were idealists, truth is only understood in its history. But whereas for Schelling and Hegel truth develops by itself, in a well-known dialectical process, on the other hand, for Dilthey a distinction must be made:

— **In physical sciences, development consists in explanation (Erklären), which is a purely rational function.

— But in human sciences, truth progresses by understanding (Verstehen) which includes the appetitive powers of the soul. Thus truth develops by the process of a vital reaction of the subject to the object, in accordance with the link of vital reaction between the historian, who looks into the facts of history, and the impact of history.

Thus, the emotive richness of the historian tends to enrich the object he studies. The subject enters into the object; it becomes a part of the object. History is charged with the energy of its readers’ emotions and thus the judgments of the past are unceasingly colored by the vital reaction of the historian or of the reader. Now, it is at the end of each epoch that there fully appears the meaning of that epoch, Dilthey emphasizes, and this is very true; from there, at each such term, it is necessary to proceed to a new revision.

Let’s apply this: the date 1962, that of the start of Vatican Council II, seemed the end of a modern epoch; thus one could then—and one was obliged to—revisit, revise all historical facts, the judgments of the past, especially concerning religion**—so as to disengage from them significant facts and permanent principles, not without coloring them anew with the preoccupations and emotions of the present.

In this sense, Hans Georg Gadamer (born in 1900) judges that the true historical consciousness does not, for the interpreter, consist in wishing to get rid of its prejudices—that would be the worst of prejudices—but in becoming aware of them and in finding better ones. This is not a vicious circle, the hermeneuticists say; it is a healthy realism which is called ‘the hermeneutical circle.’

Applied to the faith, this retrospective necessarily purifies the past from what was added in an adventitious manner to the nucleus of the faith, and this revision, this retrospective, necessarily aggregates to the faith the coloring of present preoccupations. There is, thus, a double process: on the one hand, a rereading of the past which is a purification of the past, a disengagement from its parasitic growths, a highlighting of its implicit presuppositions, a becoming conscious of its fleeting circumstances, a reckoning of the emotive reactions of the past or of the philosophies of the past; and on the other hand, it must be an enrichment of historical facts and ideas by the actual vital reaction, which depends on the new circumstances in the actual epoch, as well as upon the actual mentality and thus upon actual philosophy.

It is indeed to this hermeneutic that the expert on the Council, Joseph Ratzinger, invited the assembly in the editing of ‘schema XIII,’ which would become Gaudium et Spes, in an article written before the fourth session of the Council. What he said there about moral principles applies as well to dogmatic ones:

The formulations of Christian ethics, which must be able to reach the real man, the one who lives in his time, necessarily takes on the coloration of that time. The general problem, the knowledge that truth is only historically formulated, arise in ethics with a particular acuity. Where does temporal conditioning stop and permanent begin, so that it can, as it must, cut out and detach the first so as to arrange its vital space in the second? There is a question which no one can ever settle in advance without equivocation: no epoch can in fact distinguish what abides from its own fleeting point of view. To recognize and practice it, it is thus still necessary always to engage in a new fight. Faced with all these difficulties, we must not expect too much from the conciliar text in this matter.[19]

Benedict XVI reclaims the purification of the Church’s past

However uncertain and provisional it may be, this purification of the past is indeed what Benedict XVI reclaims for the Church, and this is a constant in his life. He says it himself:

My fundamental impulse, precisely from the Council, has always been to free the very heart of the faith from under any ossified strata, and to give this heart strength and dynamism. This impulse is the constant in my life.[20]

In his speech on December 22, 2005, Benedict XVI enumerates the purifications of the past implemented by Vatican II and he justified them against the reproach of ‘discontinuity’ while invoking historicism:

In the first place, it was necessary to define in a new way the relation between faith and modern sciences […]. In the second place, it was necessary to define in a new way the link between the Church and the modern State, which accorded a place to citizens of diverse religions and ideologies […]. This was bound in the third place to the problem of religious tolerance, a question which needed a new definition of the link between the Christian faith and the religions of the world.

It is clear – Benedict XVI concedes – that in all these sectors of which the collection forms a singular question, there could emerge a certain form of discontinuity in which, nevertheless, once the diverse distinctions between concrete historical circumstances and their demands were established, it would appear that the continuity of principles had not been abandoned.

In this process of novelty in continuity – Benedict XVI justifies himself – we should learn to understand more concretely first of all that the decisions of the Church concerning contingent facts – for example, certain concrete forms of liberalism – must necessarily be themselves contingent because they refer to a specific reality, in itself changeable: It was necessary to learn to recognize that, in such decisions, only the principles express the enduring aspect, while remaining in the background and motivating decisions from within. On the other hand, the concrete forms are not as permanent; they depend on the historical situation and can thus be submitted to changes.

Benedict XVI illustrates his proof by the example of religious liberty:

Vatican Council II – he says – with the new definition of the relation between the faith of the Church and certain essential elements of modern thought, has revisited and likewise corrected certain historical decisions, but in this apparent discontinuity, it has in turn maintained and deepened its essential nature and its true identity.

Vatican Council II, recognizing and making its own through the decree on religious liberty an essential principle of the modern State, has captured anew the deepest patrimony of the Church.[21]

When hermeneutics begins to distort history

If only Benedict XVI would allow me to protest this distortion of history! The popes of the 19th century have condemned religious liberty, not only on account of the indifferentism of its promoters, but in itself:

— because it is not a natural right of man: Pius IX said that it is not a ‘proprium cujuscumque hominis jus,’[22] and Leo XIII said that it is not one of the ‘jura quae homini natura dederit.’[23]

— and because it proceeds from ‘an altogether distorted idea of the State,’[24] the idea of a State which would rather not have the duty of protecting the true religion against the expansion of religious error.

These two motives for condemnation are absolutely general; they follow from the truth of Christ and of his Church, from the duty of the State to recognize it, and from its indirect duty to promote the eternal salvation of the citizens, not, indeed, by constraining them to believe in spite of themselves, but by protecting them against the influence of socially professed error, all things taught by Pius IX and Leo XIII.

If today, circumstances having changed, religious plurality demands, in the name of political prudence, civil measures for tolerance even of legal equality between diverse cults, religious liberty as a natural right of the person, in the name of justice, should not be invoked. It remains a condemned error. The doctrine of the faith is immutable, even if its complete application is impeded by the malice of the times. And on the day when circumstances return to normal, to those of Christianity, the same practical application of repression of false cults must be made, as in the time of the Syllabus. Let’s remember that circumstance which change application (consequent circumstances) do not affect the content of doctrine.

We must say the same thing concerning circumstances which prompt the magisterium to intervene (antecedent circumstances). That religious liberty had in 1965 a personalist context, very different from the context of aggressiveness that it had a hundred years earlier in 1864, at the time of the Syllabus, does not change its intrinsic malice. The circumstances of 1864 certainly caused Pius IX to act, but they did not affect the content of the condemnation that he set down for religious liberty. Should a new Luther arise in 2017, even without his attaching as in 1517 his 95 theses to the door of the collegial church of Wittenberg, he would be condemned in the very terms of 500 years before.[25] Let us reject then the equivocation between ‘circumstantial’ decision and prudential, provisional, fallible, reformable, correctible decision in matters of doctrine.

A new Thomas Aquinas

By consequence the purification of the past of the Church, the revision of ‘certain of her historical decisions,’ such as those which Benedict XVI proposes, is false and artificial. It is to be feared that the same goes for the assimilation by the Church’s doctrine of the philosophies of the temps, which is promoted by the same Benedict XVI in his speech to the Curia in 2005.

Benedict XVI praises Saint Thomas Aquinas for having, in the 13th century, reconciled and allied faith and the new philosophy of his epoch. This new Thomas Aquinas says: Voilà, I am going to make for you the theory of alliance which the Council has attempted between faith and modern reason. I summarize.

Here are the pope’s exact words:

When, in the 13th century, Aristotelian thought entered into contact with Medieval Christianity, formed by the Platonic tradition, and when faith and reason were at risk of entering into an irreconcilable opposition, it was Saint Thomas Aquinas who played the role of mediator in the new encounter between faith and philosophy, thus placing faith in a positive relation with the form of reason dominant in his epoch. […] With Vatican Council II the moment when a new reflection of this type was necessary arrived. […] Let us read it and welcome it, guided by a just hermeneutic.[26]

In short, Saint Thomas did not condemn Aristotelianism, despite its dangers, but he knew how to welcome, purify and establish it ‘in a positive relation with the faith.’ – This is very exact. – Very well, then, Vatican II did analogously; it did not condemn personalism, but it knew how to receive it, and , in return for some purifications, ‘how thus to place the faith in a positive relation with the dominant form of reason’ in the 20th century, how to integrate personalism into the vision of the Church. – Stay to see whether this integration is possible.

Chapter 2

Joseph Ratzinger’s Philisophical Itinerary

From Kant to Heidegger: a seminarian’s intellectual itinerary

What then is this ‘dominant form of reason’ which seduced the young Ratzinger and challenged his faith, so much so that he must exert himself heroically to reconcile them? Just like what he studied as a young cleric, it comes out of the agnosticism of Immanuel Kant (1724-1804).

For the philosopher of Koenigsberg, our universal ideas do not take their necessity from the nature of things, which is unknowable, but from reason alone and from its innate ‘a priori categories’ of substance, causality, etc. Reason alone gives its structure and intelligibility to the real.

We only know a priori [that is to say, in a necessary manner] those things which we put there ourselves [Kant affirms].[27]

Modern physical science already followed this idealism with fruit by maintaining that the nature of the physical world remains opaque to reason and that we can only have mathematical and symbolic representations for it, in scientific hypotheses, works of reason, which force nature to appear before its tribunal so as to constrain it, by experimentation, to confirm the judge’s a priori. Once confirmed, the hypothesis is declared scientific theory, but it remains nonetheless a provisory and always perfectible hypothesis.

Kant wants to apply this rationalism to the knowledge of the operations of the intelligence itself upon the givens of sensible knowledge. It is our understanding, he says, which applies its a priori categories to things.

He does not see that the real beings most immediately perceived by the intelligence, such as being itself, or substance, or the essence of a thing, are on the contrary intelligible by the simple abstraction which the intellect operates on them from the givens of sensible experience. In particular, the first thing known by our intelligence is the being of sensible things:

What is first conceived by the intellect is being; for everything is capable of being known according as it is in act […]. This is why being is the proper object of the intellect; it is thus the first intelligible, as sound is the first object of hearing.[28]

And upon this apprehension of being is founded the natural knowledge of the first principles: being is not non-being; everything which happens has a cause; every agent acts for an end; all nature is made for something, etc.

On the contrary, the consequences of the Kantian ‘unknowning’ or agnosticism are catastrophic: being as being is unknowable; the analogy of being is indecipherable and the principle of causality has no metaphysical value; thus one cannon prove the existence of God from the things of the world, and any such analogy between creature and Creator is unknowable, even blasphemous.

Kantian agnosticism, father of modernism

Consequently, reason cannot know either the existence or the perfections of God. This agnosticism even so incurs this reproach from Wisdom:

Deranged by nature are all men in whom there is not the knowledge of God and who, from visible goods, have not known how to understand He who is, nor, by the consideration of his works, how to recognize by analogy Who is their creator.[29]

Likewise, since the analogy with God is impossible, the revealed analogies which unveil for us his supernatural mysteries are just metaphors; consequently, every word of God can only be allegorical, and all human discourse concerning God, inversely, can only be mythological. This is the same principle of modernism condemned by Saint Pius X a century later: evangelical facts result from fabrications, and dogmas from a transfiguration of reality because of religious need. Dogmas have a practical and moral meaning which answers to our religious needs, while their intellectual meaning is derivative and subordinated. Their generative principle is within man; it is the principle of immanence.[30] For example, for Kant, already, the Trinity symbolize the union in a single being of three qualities of goodness, holiness and justice; the incarnate Son of God is no supernatural being; he is a moral ideal, that of a heroic man.[31] Therefore, dogmas are nothing more than symbols of states of soul.

The autonomy of practical reason, mother of the Rights of Man-without-God

On the other hand, in morality, according to common sense, human nature and its natural operations are defined by their ends, just as the nature and way of using a washing machine are what they are by their end. Well, Kant rejects the principle of finality itself, true and thereby the knowledge of our nature. He ignores that this nature is made for happiness and that true happiness consists in seeing God, who is the sovereign Good. Moreover, he denies the analogy between the sensible good, object of desire, and the genuine good, the will’s goal according to the perennial philosophy. The notion of the good is not acquired from sensible experience, and the existence of the sovereign Good is unknowable. Then what about morality? For Kant, a good act is not that which has an object and an end conformed to (unknowable) human nature and which of itself ordains man to the last end, but it is to act independently of every object and every end, out of pure duty, which is pure good will:

A good will is good not because of what it effects or accomplishes, nor because of its fitness to attain some proposed end; it is good only through its willing, i.e., it is good in itself.[32]

This is really the refusal of the final cause, the negation of the good as the end of our acts and the exclusion of God as sovereign Good and sovereign legislator. It is the proclamation of ‘the autonomy of practical reason.’ It is the German theory for the French Rights of Man in 1789. It is man taking the place of God.

Kantian virtue acts so as to ‘maintain in a person his humanity with its dignity.’[33] And as any such virtue, quasi stoical, does not coincide here below with happiness, it postulates the existence of a God who makes remuneration in the next life, a provisional and hypothetic Deus ex machina, concerning whom ‘one can only affirm that he exists apart from the rational thought of man.’[34]

Reconciling the Enlightenment with Christianity

Even if he seems to reprove such a ‘religion within the limits of reason alone,’ Joseph Ratzinger admires Kant, the philosopher par excellence from the Enlightenment. He salutes ‘the enormous effort’ of one who knew how ‘to bring out the category of the good’—that beats everything!—He proclaimed the current import of the Enlightenment, in his discourse at Subiaco, on April 1, 2005, one month before becoming pope. He analyzed the contemporary culture of the Enlightenment as being that of the rights of liberty, of which he enumerated the principles while adding**:

– “This canon of Enlightenment culture, though far from being complete, contains important values from which, as Christians, we cannot and we must not disassociate ourselves. […] Undoubtedly, we have come to important acquisitions which can aspire to a universal value: the established point that religion cannot be imposed by the State but can only be welcomed into liberty; respect for the fundamental rights of man, which are the same for all; separation of powers and the control of power.”

– But, Joseph Ratzinger nonetheless objects, this Enlightenment culture is a secular culture, without God, anti-metaphysical because positivist, and based upon an auto-limitation of practical reason by which ‘man allows for no instance of morality independent from his self-interest.’ Consequently, ‘there exists contradictory Rights of Man, as for example the opposition between a woman’s wish for freedom and the embryo’s right to life. […] An ideology confused with liberty leads to a dogmatism always very hostile to liberty.”[35] By its absolute, this ‘radical Enlightenment culture’ is opposed to Christian culture.[36]

– How to overcome this opposition? Here is the synthesis:

On the one hand, Christianity, religion of logos, according to reason, must rediscover its roots in the first philosophy from the Enlightenment, which was its cradle and which, abandoning myth, sought for truth, goodness and the one God. In return for this, this nascent Christianity ‘refused to the State the right to regard religion as a part of the political order, postulating thus the liberty of the faith.’[37]

On the other hand, Enlightenment culture must return to its Christian roots. But of course: proclaiming the dignity of man, a Christian truth, ‘Enlightenment philosophy has a Christian origin, and it is not haphazardly that it was rightly born in the domain of the Christian faith’ (sic).

This, moreover, the future Benedict XVI underlines, was the work of the Council, its fundamental intention, exposed in its declaration concerning ‘the Church in the modern-day world,’ Gaudium et Spes:

[The Council] has placed in evidence this profound correspondence between Christianity and the Enlightenment, trying to arrive at a true reconciliation between the Church and modernity, which is the great patrimony which each of the two parties must safeguard.[38]

To do this, Kant, in spite of his agnosticism, must be taken into account, the future pope judges: every man, even the unbelievers, can postulate the existence of God:

Kant denied that God can be known within the limits of pure reason, but at the same time he represented God, liberty and immortality, as so many postulates of practical reason, without which, he said in perfect agreement with himself, no moral act is possible. Does not the contemporary situation of the world make us think again that he might have been right?[39]

In search of a new realist philosophy

From his first love, never renounced, for Kant, the intellectual itinerary of a young seminarian from Freising led Joseph Ratzinger to modern German philosophy. He recounts it in his memoirs. Counseled by my elder, Alfred Läpple, he said, ‘I read two volumes of the philosophical foundations for Steinbüchel’s moral theology, a new edition of which had just been prepared.’

[In this book, he continues,] I found first of all an excellent introduction to the thought of Heidegger and Jaspers, as well as to the philosophies of Nietzsche, Klages and Bergson. For me, Steinbüchel’s work, The Revolution of Thought, was nearly the most important. Just as one believes in physical power so as to abandon a mechanistic conception and establish a new opening into the unknown and consequently into ‘the known Unknown,’ God, so one can note, in philosophy, a new return to the metaphysics made inaccessible after Kant.

We know that the physicist Werner Karl Heisenberg (1901-1976) elaborated in 1927 a theory concerning the statistical position of atomic and molecular particles known by the name of the ‘uncertainty principle.’ In 1963, our professor of physical sciences in Paris, Monsieur Buisson, mocked the application, that certain ill-advised philosophers wanted to make of this principle, to substance and nature, which must henceforth be considered indeterminate and thus instable! It is unbelievable to see how the confusion between substance and quantity can have put the pseudo-philosophers, and even the pseudo-theologians, in a whirl for fifty years.

Steinbüchel, who began by studying Hegel and socialism, exemplified in the cited work the blossoming of personalism essentially due to Ferdinand Ebner, who also acted for him as a turning point in his intellectual development. The discovery of personalism, which we find realized with a new force of conviction in the great Jewish thinker, Martin Buber, was for me a marked intellectual experience; this personalism was by itself linked in my eyes to the thought of Saint Augustine, which I discovered in the Confessions, with all his human passion and depth.[40]

Relapse into idealism: Husserl

The turning point of modern thought is marked by phenomenology. Edmund Husserl (1859-1938), a professor at various German universities, wanted to react against Kantian idealism and come ‘to things themselves.’ Very well. But to reach undeniable truth, he practiced a sort of methodical doubt, ‘épochè,’[41] which in Greek signifies the suspension of judgment, and he ‘struck into nothingness’ whatever was not ‘authentic.’ He did not deny the existence of external things, but he put it ‘between parentheses’: thus experience was ‘reduced’ to what is ‘give,’ to what appears, to what manifests itself ‘authentically.’ Well, the demand of this process lead Husserl to profess provisionally the contrary of what he had expected: it is no longer the thing external to the spirit which is absolutely real, but it is the ‘given,’ that is to say, the reality of my act of aiming at my mental object, in which I know myself to be thinking something.

For consciousness – Husserl says – the given is essentially the same thing, whether the represented object exist, or whether it be imagined or even perhaps absurd.[42]

It is clear in any case that everything which is in the world of things is, by principle, only a presumed reality for me. On the contrary, myself […], or if you like the actuality of my existence, is an absolute reality. […] Consciousness considered in its purity must be held by a system of being closed on itself, by an absolute system of being.[43]

Curiously, we find at the same time in modernism, the same disinterest in reality applied to religion: the reality of the mysteries of the faith matters little; what is important is that they express the religious problems and needs of the believer and help him to resolve them or to fulfill them. It was Alfred Loisy (1857-1940), Husserl’s exact contemporary, who undertook this ‘reduction’ on the part of dogma. These ideas were in the air.

With Husserl and his extreme crisis of idealism, the ‘turning point of thought’ evoked by Joseph Ratzinger was still problematic.

Heidegger’s existentialism

Let us understand the atmosphere of fresh air that existentialism, such as that of Heidegger, professor at Fribourg-en-Brigsau, can bring. Martin Heidegger (1889-1976) wanted to avoid Husserl’s relapse into idealsm; he consecrated himself to beings, whose existence—the fact that they are cast into existence—calls out to us. At last, you say, here we leave the ideal and plunge again into the real! Alas! Being above all is the person and the general conditions for his affirmation. For existentialism in general, to exist is to have oneself abandon what one is not, by a free choice of destiny; in this sense, ‘existence precedes essence,’ becoming precedes being. To define the nature of things is determinism. – Kantian agnosticism is alive and well! The difference is that being defines itself by its action, as in Maurice Blondel (1861-1949).

For Heidegger, the subject is not constituted statically, by its nature, but by its dynamism, by its connections with others. Cast into existence and exposed to the abrupt impression ‘of finding myself there’ and to the feeling of ‘dereliction,’ I deliver myself from my anguishes by casting ahead, by accepting my destiny courageously and by making the decision to assume my place in the world, to ‘exceed myself,’ by giving my whole self to others who exist with me and by granting them authentic being.

Joseph Ratzinger will apply the idea of excelling oneself as accomplishment of self to Christology: Christ will be the man who completely excels, by the hypostatic union, and again, differently, by the cross.

Max Scheler’s philosophy of values

Another of Husserl’s disciples, Max Scheler (1874-1928), a professor at Frankfort, is the founder of the philosophy of values. According to this theory, human and community life is directed not by principles—which reason abstracts from the experience of things and which are founded on human nature, its finality and its Author—but by a state of spirit, a sense of life and of existence, which is nonetheless illuminated by immutable and transcendental values, which are imposed a priori (as Kant would say): liberty, person, dignity, truth, justice, concord, solidarity. These are the ideals, the many ideas which should live in action, in commitment to the serve of others and by which all should commune, differently however according to cultures and religions.

The Council, John Paul II and Benedict XVI are imbued with this philosophy of values.

The Council proposed before all to judge by its light (of the faith) the values most prized by our contemporaries and reconnect them to their divine source. For these values, in so far as they proceed from the human genius, are very good.[44]

The Church should not be the only promoter of values in civil society. […] Ecclesiastical participation in the life of the country, by an open dialogue with all other forces, guarantees to Italian society an irreplaceable contribution of great moral and civil inspiration.[45]

It would be absurd to wish to turn backwards, to a Christian political system […]. We do not hope to impose Catholicism on the West. But we do wish that the fundamental values of Christianity and the liberal values dominant in the world today could meet and become fertile mutually.[46]

This is to suppress the final cause along with the efficient cause of man and of society, and to construct politics on pure Kantian formalism.

Personalism and communion of persons

Scheler is the originator of a Christian existentialism or personalism. On the basis of the same confusion between being and act which is characteristic of Blondel and Heidegger, Scheler affirms that the ‘I’ results from the synthesis of all my vital phenomena of knowledge, instinct, emotion, passion, especially love—a synthesis which transcends each of these phenomena by an ‘unknowable something more’ In this superior value the person discovers itself as ‘the concret unity of being in its acts.’ The person exists in his acts.

Love makes the person reach his ‘highest value,’ in an intersubjectivity where love shares in the life of the other and makes them interdependent. The Council was inspired by this to declare:

Man, the only creature upon the earth that God willed for its own sake, can only find himself fully in the disinterested gift of himself.[47]

There is the phenomenological view of charity, most characteristic of Scheler. But the danger is to reduce the redemption to an act of divine solidarity. Joseph Ratzinger will fall into this failing. Max Scheler goes only to the point of affirming that God has need of communicating himself to others, otherwise the disinterested solidarity which is the essence of love would not be authentic in Him. Joseph Ratzinger will apply this excess of intersubjectivity to the processions of the divine persons in the Trinity.

According to Scheler, the person is not only individual and ‘unrepeatable,’ but also plural and communal. It is of his essence to become part of a community which is a Miterleben, a ‘living with,’ a communion of experience.

Karol Wojtyla (1929-2005), the future Pope John Paul II, was an ardent disciple of Scheler, for whom he wished to supply his nonexistent[48] ethics, without correcting his metaphysic of the person. For Wojtyla, ‘the person determines himself by his communion (or participation, communication, Teilhabe) with other persons.”[49] The person is relation, or tissue of relations.

Isn’t this nonsense? The person, philosophically speaking, is a substance par excellence and not an accident or a collection of accidents. “The person is most perfect in its nature,” Saint Thomas explains.[50] It is evident that this ‘perfection’ is to subsist in itself and not in any other. Invaluable then is Boethius’ definition of person, maintained by Saint Thomas: “Hoc nomen persona significat subsistentem in aliqua natura intellectuali: the name ‘person’ signifies a being subsisting in an intellectual nature.”[51]

Well, abandoning such healthy realism, all personalism adopts the relational definition of the person. And the application of this definition to social life seems to flow from the source: communion, Wojtyla said, is not anything which reaches the person from the exterior, but the very act of the person, which energizes it and reveals to it, through unity with the other, its interiority as a person.[52] The Council picks up this idea:

The social character of man becomes apparent by the fact that there is an interdependence between the growth of the person and the development of society itself. In fact the human person […a Thomistic interpolation] is and must be the principle, the subject and the end of all institutions. Social life is not therefore for man something superfluous: as it is by exchange with others, by the reciprocity of services, by dialogue with his brothers that man grows according to all his capacities and can answer to his vocation. [Gaudium et Spes, #25, § 1]

We will see further this application of this principle to the Church and to political society: if the person itself constitutes society, it follows that one could even have economics as the final cause for society, unless the person be first made the end of society.

The dialogue of ‘I and Thou’ according to Martin Buber

Joseph Ratzinger has recounted how, by means of reading Steinbüchel, he made the acquaintance of ‘the great Jewish thinker, Martin Buber.’[53] ‘The discovery of personalism […] realized with a new force of conviction’ in Buber was for Ratzinger ‘a marked spiritual experience.’[54]

The central work of Martin Buber (1878-1965), I and Thou (Ich und Du, 1923), places relation at the beginning of human existence.

This relation is either ‘I-it,’ as in the technical sphere, or ‘I-thou.’ The ‘I-it,’ in human relations, reduces a fellow man to a thing, considered as a mere object or a simple means. On the contrary, the ‘I-thou’ establishes with another a reciprocity, a dialogue, which supposes that I, at the same time as the other, am a subject. Buber is the thinker of intersubjectivity. If the ‘I*-it’ is necessary or useful for the functioning of the world, only the ‘I-thou’ sets free the ultimate truth of man and thus opens a true relation between man and God, the eternal Thou.[55]

The relation to others, who hold the common nature of man, is important, with its power, authority, influence, appeal, invitation, answer, obedience, but the danger is to make this relation the constituent of the person, when it is only one of its perfections. Besides, in this matter Buber discovered nothing, since already Aristotle (384-322 BC) set friendship as the virtue which crowns intellectual life and happiness. He defined it as ‘a mutual love founded on the communication of some good,”[56] as Saint Thomas (1225-1274) said, which, going even beyond Buber, makes charity (love of God) a true friendship:

As there is a certain communication of man with God, according as he communicates to us his beatitude, this communication must be founded upon a certain affection. Concerning this communication it is said in the first epistle to the Corinthians (1, 9): “God is faithful, by whom you are called into the fellowship of his Son, Jesus Christ our Lord.” In fact, the love founded upon this communication is charity. It is thus manifest that charity is a certain friendship of man for God.[57]

Moreover, the danger, in the religious domain, is to confuse this charity with faith and to make faith in God a dialogue of the believer with a God who ‘cries out to him,’ making an abstraction from the conceptual content of the faith, that is to say, from the truths that God has revealed—not to me, but to the prophets and Apostles—and that the Church teaches. See how Buber himself confuses Revelation, experience, encounter, faith and reciprocal relation.

Revelation is the experience which swoops down on man in an unexpected manner […]. This experience is an encounter with an eternal Thou, with an Altogether-Other who addresses himself to me, who calls me by my name […]. The image of encounter precisely translates the essence of religious experience. The Thou as an active and not objectifiable presence, comes to meet me and expects for me my establishment in the faith of reciprocal relation.[58]

It is to be feared that Joseph Ratzinger made this confusion between faith, Revelation and reciprocal relation, and that he also abstracted from the content of the faith, that is to say, from revealed truths. It is this that the continuation of my exposé will try to elucidate, first by examining Joseph Ratzinger’s theological itinerary, then by a more precise study of the notion of faith which the future Benedict XVI developed in the course of his career. But before that, let’s look at one last philosopher who interested the student in Munich.

‘Going Out of Self’ according to Karl Jaspers

By Joseph Ratzinger’s own avowal, there was in fact another existentialist and personalist, Jaspers, who marked the young philosopher of Freising.

Karl Jaspers (1883-1969), a professor at Heidelberg, resembles a Christian existentialist and personalist, although he did not know how to reflect on the personality of God. He proposed an natural analogy for charity toward fellow men: communion. He is in fact less original in comparison with Scheler and Heidegger. He notes the experience of loving communication, made out of respect for the mysterious personality of the ‘other’ whom one even so wishes to touch and to whom one wishes to give oneself. This going out of self (Ek-Stase) towards others would furnish to Joseph Ratzinger a philosophical substratum for the considerations of Dionysius’ mystical theology concerning the ecstatic love of the soul for God and for a new interpretation of the redemptive love of Christ, as ‘going out of myself,’ in reaction to the pessimism of Heidegger for whom ‘going out of self’ is the solution for the anguish of an existence doomed to death.

Christ—Joseph Ratzinger will teach at Tübingen—is fully anthropocentric, fully ordained to man, because he was radically theocentric, in yielding the ego, and by this fact the being of man, to God. Then, in the measure by which this exodus of love is the ‘Ek-Stase’ of man outside of himself, an ecstasy by which he is extended forwards infinitely outside of himself and thus opened, is drawn beyond his apparent possibilities for development—in this very measure adoration [sacrifice] is simultaneously cross, suffering and heartbreak, the death of the grain of wheat which can bring forth no fruit until it passes through death.[59]

Is this not to effect a personalist or existentialist reinterpretation of the redemption? The cross should not be the torture of Jesus on the wood of the cross; without doubt it is not, as with Heidegger, an extension into the future so as to escape the present; but it is the extension outside of self for the sake of love which ‘shatters, opens, crucifies and sunders.’[60] In this fatally naturalistic perspective, where is sin? Where is atonement?

The danger of wishing, with Heidegger or Jaspers, to find natural and existential bases for supernatural realities is that of succumbing to a temptation all too natural for a spirit which seeks to reconcile ‘modern reason’ with the Christian faith: to cause, in place of an aspiring analogy, a debasing reduction of supernatural mysteries. Was this not the process of Gnostic heresies?

Jaspers exceeds the rest in the fault of confusing natural with supernatural. His method of ‘paradoxes’ consists in finding for the apparent contradictions of the natural order supernatural solutions. John Paul II seems to have given in to this fault in his encyclical on August 6, 1993, concerning the norm of morality: his letter presents itself as the modern solution for a modern antinomy:

How can obedience to universal and immutable moral norms respect the unique and unrepeatable character of a person and not violate its liberty and dignity?[61]

Dignity is considered in a personalist manner, as inviolability, and not in a Thomist manner, as virtue. Thus, to a false problem, a false solution:

The crucified Christ reveals the authentic meaning of liberty: the total gift of self. [VS 85]

The gift of self in the service of God and of one’s brothers [accomplishes] the full revelation of the inseparable link between liberty and truth. [VS 87]

This is true on the supernatural level. But isn’t it disproportionate to give a philosophical question a supernatural, theological solution: the cross? The true solution of the antinomy is the Thomistic: liberty is the faculty which pursues the good; and it is the role of moral law to indicate what is this good, and that’s all.

This false antinomy reveals a subjectivist philosophy’s incapacity to pose true questions. How to grasp the mystery of God, if the intellect has that for its first object how, not being, but the thinking subject or the questioned subject? If the notion of being does not allow one to climb again by analogy from created beings to the first Being? One is forced into the immanent genesis of dogmas, according to the modernist theory condemned by Pascendi. How to grasp the notion of good, the ratio boni, if thought cannot climb by analogy from sensible good to moral good? If the intellect does not know human nature and its ends, and the last end? One is condemned to the ethics of the person, the ethics of the inviolable subject or rather that of the subsistent relation. On all sides, there is an impasse.

Chapter 3

Joseph Ratzinger’s Theological Itinerary

Joseph Ratzinger’s philosophical itinerary is then an impasse, because it abandons the road of the philosophy of being. Will the theological itinerary of the same Ratzinger leave that impasse? Will it find a way which leads to the first Being, to his infinite perfections, to his supernatural mysteries?

To answer this question, it is first necessary to situate the professor of Tübingen in the context of German theology, dependent on the celebrated school of theology in the university of that very city.

Living Tradition, continuous Revelation, according to the school of Tübingen

According to the founder of the Catholic school of Tübingen, Johann Sebastian von Drey (1777-1853), historical development is explained by a vital spiritual principle:

What encloses the various historical epochs into a united whole or what sets them in opposition to each other is a certain spirit which, at determined times, concludes historical development with a unity filled with life: this is the Zeitgeist, the spirit of the age.

[This spirit is constructive:] acting by going out of itself, it draws everything around itself like the center of a circle, which reduces opposition and reorganizes in accordance with itself whatever is conformed to it.[62]

The affinity of this thought to Dilthey’s is striking, but for Drey, the Zeitgeist is nothing besides the spirit of Christ. The theologian’s faith transfigures the philosopher’s naturalism.

In his Apologetik (1838), Drey explains how evolution is necessary to Chrstianity, insofar as it is a historical phenomenon and insofar as it is Revelation. Here is how Geiselmann summarizes Drey:

Christian Revelation is life, originally divine life—a life which, without interruption, increases from its original core towards its plenitude within the universal Church. As uninterrupted divine life, Revelation is not a completed gift, deposited, so to speak, in the cradle of the church and transmitted by human hands. It is this very Revelation, which, like all life, moves and continues of itself.[63]

Its movement is auto-movement, thanks to that portion of spiritual force which has dwelt in it since its origin, to know God’s essential force and also his action, which, without failing, continues to act and to lead his creation towards its perfection.[64]

Revelation, living Tradition and evolution of dogma

This idea of Revelation, which ‘no longer appeared simply as the transmission of truths addressed to the intellect, but as the historical action of God, in which Truth unveils itself little by little,’[65] would have been the thesis concerning Saint Bonaventure presented by Joseph Ratzinger in 1956 for his State authorization as a university professor. The author pretended that the Seraphic Doctor had seen in Revelation, not an ensemble of truths, but an act (which is not exclusive), and that ‘the concept of “Revelation” always implies the subject who receives it’[66]: the Church thus forms a part of the concept of Revelation, that is to say, a part of Revelation itself. Similarly, the candidate for authorization maintained that ‘to Scripture belongs the subject who understands it [the Church]—Scripture with which we have already given the essential meaning of Tradition.’[67] And Joseph Ratzinger tells just how his thesis-director, professor Michael Schmaus, ‘did not at all see in these theses a faithful reconstruction of Bonaventure’s thought […] but a dangerous modernism, well on the way to turning the concept of Revelation into a subjective notion.’[68]

Well, this idea of Revelation as a divine intervention in history, which also was not closed by the death of the last of the Apostles, but which continues in the Church which is its receptive subject, had been rejected meanwhile, after Drey and before Loisy, by the Roman magisterium: Revelation is not any divine intervention, but only a pronunciation from God, ‘locutio Dei,’[69] not to the whole Church, but to ‘the holy men of God’ (1 P 1, 21), the prophets and Apostles’; the truth which it contains ‘was complete with the Apostles’[70]; it is not perfectible,[71] but is a ‘divine deposit’ confided to the magisterium of the Church ‘so that it might guard it as sacred and set it out faithfully.’[72]

The ‘Revelation transmitted by the Apostles, or the deposit of the faith’[73] does at all times experience progress, not indeed in its content, of which the Apostles possessed the plenitude as well as the plenitude of understanding[74], but in its explanation, by a ‘more ample interpretation’[75] or a clearer ‘distinction,’[76] that is to say, by a passage from implicit to explicit[77] of that same deposit of faith closed at the death of the last of the Apostles.

Certainly, God continues to intervene in human history: the conversion of the emperor Constantine, the evangelization of America, the pontificate of Pope Saint Pius X were as milestones among so many others in God’s providential action, but they do not have the value of divine Revelation. Here a very important distinction must be made: a progressive Revelation from God is undeniable in the Old Testament and even in the New until the death of Saint John. After that, public Revelation ended. Neither God nor anyone else could add anything whatsoever to it, as Saint John said in the Apocalypse:

For I testify to everyone that heareth the words of the prophecy of this book: If any man shall add to these things, God shall add unto him the plagues written in this book. And if any man shall take away from the words of the book of this prophecy, God shall take away his part out of the book of life, and out of the holy city, and from these things that are written in this book. [Apoc. 22, 18-19]

Without doubt, as Saint Thomas says, ‘in each epoch, the Church never lacks men filled with the spirit of prophecy, not indeed to draw out a new doctrine of faith, but for the direction of human acts.’[78] These are the subjects and instruments of private revelations. If, therefore, anyone supposes that public Revelation is continued in the Church by the prophetic charism of its members or of the hierarchy, he falls into error. Here as elsewhere, Saint Thomas is a sure guide. Speaking of the Old Testament, he teaches that there has effectively been an increase in the articles of faith, not as regards their substance, but as regards their explanation:

As regards the substance of articles of faith, there has been no increase in these articles according to the succession of time, because all the later ones are believed to have been already contained in the faith of the early Fathers albeit implicitly. But as regards their explanation, the number of articles as increased: because certain among them have been explicitly understand by the successors, which were not explicitly understood by the first. Thus, the Lord said to Moses in Exodus: ‘I am the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, the God of Jacob and my name of Adonai I did not tell them.’ And the Apostle says: ‘the mystery of Christ…in other generations was not known…as it is now revealed to his holy apostles and prophets’ (Ep. 3, 4-5)[79]

There is no parallel but only analogy between the time of Revelation and the time of the Church, between progressive Revelation, on the one hand, and progressive development of Christian dogma, on the other. Thus Saint Bonaventure must be interpreted. Until Christ and the Apostles, Revelation itself was developed while passing from implicit to explicit; after the Apostles, Revelation being terminated, its understanding, its application and its proposal by the Church are developed while passing from implicit to explcit.

We could summarize this in Latin: Ante Christum, creverunt articula fidei quia magis ac magis explicite a Deo revelata sunt; post Christum vero et apostolos, creverunt quidem articula fidei quia magis ac magis explicite tradita sunt ab Ecclesia.[80]

Tradition, a living interpretation of the Bible

The historicism in Joseph Ratzinger’s concept of Tradition presupposes his subjectivism. The mystery of God is not an object; it is a person, an I who speaks to a Thou. The I who speaks is only perceived by a Thou who listens. This relation is inscribed in the notion of Tradition. Tradition, consequently, is nothing besides the living interpretation of Scripture:

There can be no pure sola scriptura (‘by Scripture alone’). To Scripture belongs the subject who understands it—Scripture by which is already given to us the essential meaning of Tradition.[81]

This requires explanation. For idealist thought, the crude thing is unknown; it is the object (that is to say, the thought thing) which is known. For Kant, the subject forms a part of the object, imposing on it his a priori categories, his own coloring. For Husserl, the thought object is simply the correlative for the thinking subject, independent of the thing. Joseph Ratzinger would find an application of this idealism in Scripture and Tradition: crude Scripture is unintelligible; it must be ‘understood’ by the Church as subject, which is its correlative, and which interprets it in its own manner; in this sense, ‘there can never be Scripture alone,’ in rebuttal of what Luther pretended with his ‘sola scriptura.’

In fact, Joseph Ratzinger is here inspired by Martin Buber,[82] for whom the essence of the Decalogue is a summons: the summons of the human Thou by the divine I: ‘Thou shalt not have strange gods before me…’ (Ex. 20, 3). Interpretation of the Bible relives the experience of this summons. In this sense, there is no sola scriptura since there is always the summons, today in the Church.

The truth is that it is the Church who gives an authentic interpretation for the Bible. But this is not because she is ‘the understanding subject,’ but because she is its judge: ‘It belongs to her to judge concerning the true meaning and interpretation of Holy Scripture.”[83] And to sustain this judgment, the Church has another source of faith: Tradition, that is to say, the truths of faith and morals received by the Apostles from the very mouth of Christ or from the holy Ghost, which have been transmitted from them to us without alteration, as though from hand to hand.[84] The witnesses for Tradition are the holy Fathers, the liturgy, the dispersed and unanimous magisterium of the bishops and the magisterium of councils and popes. All these voices succeed each other, but Tradition in essence is immutable.

It is because it is immutable that it can be a rule for the faith, because elastic rules are no rules at all. It is therefore insofar as it is immutable that Tradition is a rule of interpretation for the Bible; there is no actual reading of the Bible, different from yesterday’s, which can suffer Scripture to undergo a ‘process of reinterpretation and of amplification,’ as Benedict XVI pretends.[85]

Immutable in itself, Tradition progresses in becoming more explicit. Here is a truth which Vatican Council II, in its constitution Dei Verbum concerning Divine Revelation, has obscured by alleging an historical progress for Tradition in ‘its perception’ and in ‘its understanding’ of the things revealed by God, and an ‘incessant tendency of the Church towards the plenitude of divine truth’—things absolutely impossible, as I have shown. I cite: